The 2023 Giro d’Italia has come to an end. After over 85 hours of racing covering almost 3500 kilometres, Primož Roglič emerged victorious by a margin of 14 seconds over the runner up, Geraint Thomas.1,2 We have previously covered the physiological demands and energy expenditure of riding a Grand Tour. Instead, this piece will look at the training leading up to the Giro of three riders that finished in the top 5.

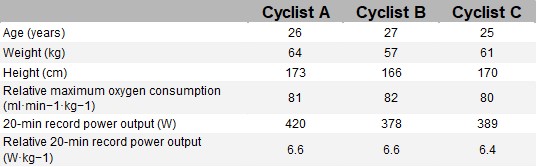

The Giro d’Italia consists of 21 stages covering ~3500 kilometres and ~50,000 metres of altitude gain, with only 2 rest days during the race.2 In 2022, a case study of three professional cyclists who achieved a top 5 in the general classification between 2015-2018 described the training diaries in the 22 weeks leading up to the race.3 The anthropometric and physiological characteristics of the three cyclists have been outlined below in Table 1.

Table 1. Anthropometric and physiological characteristics of the cyclists. Adapted from Gallo et al. (2022).3 (CC BY 4.0).

Training volume and intensity distribution

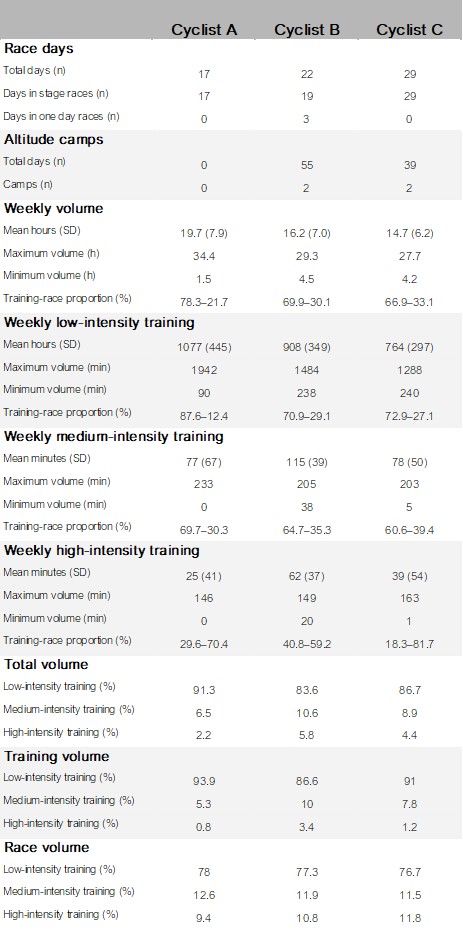

A summary of the training and racing data has been outlined in Table 2. The average training volume was about 15-20 hours/week, with individual weeks reaching almost 35 hours, meaning that the cyclists did not adopt exceptional training volumes when compared to training diaries from other professional cyclists.4

The study used a three-zone intensity system, where zones 2 and 3 were demarcated by the functional threshold power (FTP; calculated as 95% of the maximum 20-minute power), and the threshold between zone 1 and 2 was set to 85% of the FTP. Training in each zone is referred to as low (LIT), medium (MIT), and high (HIT) intensity training. Most of the training was conducted in zone 1 (87-94%), with 5-10% in zone 2, and the least in zone 3 (~1.5%). To allow for high training volumes, the athletes are forced to keep the intensity relatively low to avoid overtraining.5

All three cyclist partook in multiple races leading up to the Giro, favouring multi-day stage races over one day races to mimic the demands of the Giro. During race weeks, the intensity distribution shifted towards more HIT and less LIT, leading to a sort of “high-intensity races-based block periodisation”. Racing, as opposed to HIT, enhances motivation and lowers the perception of effort, which was reportedly a reason for these racing blocks.

Table 2. Training and racing characteristics of the cyclists leading up to the Giro. Adapted from Gallo et al. (2022).3 (CC BY 4.0).

Tapering

Tapering is the act of reducing the training load in the period preceding a competition to optimise performance. The general recommendation is to reduce the training volume by 40-60% in the final 2 weeks without altering training intensity and frequency.6

The three cyclists adopted a tapering protocol leading up to the Giro. In week -2 and -1, they reduced the volumes by 7% and 21%, 22% and 8%, and 64% and 8%, whilst drastically increasing the proportion of HIT. This is substantially less than the general recommendations, but in line with previously reported tapering strategies in world class athletes.7

Altitude training

Altitude training is regularly adopted by elite athletes to improve performance at altitude and sea level. Lower oxygen levels cause the body to increase haemoglobin mass (amongst other things), leading to an improved oxygen carrying capacity from the lungs to the muscles.8 Generally, athletes are recommended to conduct their altitude training for periods lasting >2 weeks at 1800-2500 metres above sea level.9

Cyclist A did not conduct any altitude training leading up to the Giro. Cyclist B and C both completed two altitude training camps lasting 2-4 weeks at an altitude of ~2800 metres above sea level. Cyclists B and C, both high-altitude natives, followed a classic altitude training protocol where they both trained and slept at the same altitude.

Strength training

Strength training in order for endurance athletes to optimise performance has been a matter of debate for a long time. Emerging evidence indicates that heavy and explosive strength training can be implemented successfully in elite-athletes and enhance performance by improving exercise economy.10

Despite the coaches’ indications, the three cyclists did not perform any strength training.

Summary

Leading up to the Giro d’Italia, the three top 5 finishers adopted a fairly normal training regimen of 15-20 hours of weekly training with most of it being LIT. The tapering strategy differed from the general recommendations and altitude training was used by two of the three cyclists. Despite encouragement, the cyclists were unwilling to perform any strength training.

References

- Rankings of the Giro d’Italia 2023. Giro d’Italia 2023. Accessed May 28, 2023. https://www.giroditalia.it/en/classifiche/

- Giro d’Italia 2023 route and stages. Giro d’Italia 2023. Accessed May 28, 2023. https://www.giroditalia.it/en/the-route/

- Gallo G, Mateo‐March M, Gotti D, et al. How do world class top 5 Giro d’Italia finishers train? A qualitative multiple case study. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2022;32(12):1738-1746. doi:10.1111/sms.14201

- Sandbakk Ø, Haugen T, Ettema G. The Influence of Exercise Modality on Training Load Management. International Journal of Sports Physiology and Performance. 2021;16(4):605-608. doi:10.1123/ijspp.2021-0022

- Seiler S. What is Best Practice for Training Intensity and Duration Distribution in Endurance Athletes? International Journal of Sports Physiology and Performance. 2010;5(3):276-291. doi:10.1123/ijspp.5.3.276

- Bosquet L, Montpetit J, Arvisais D, Mujika I. Effects of Tapering on Performance: A Meta-Analysis. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise. 2007;39(8):1358. doi:10.1249/mss.0b013e31806010e0

- Tønnessen E, Sylta Ø, Haugen TA, Hem E, Svendsen IS, Seiler S. The Road to Gold: Training and Peaking Characteristics in the Year Prior to a Gold Medal Endurance Performance. PLOS ONE. 2014;9(7):e101796. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0101796

- Mujika I, Sharma AP, Stellingwerff T. Contemporary Periodization of Altitude Training for Elite Endurance Athletes: A Narrative Review. Sports Med. 2019;49(11):1651-1669. doi:10.1007/s40279-019-01165-y

- Saunders PU, Pyne DB, Gore CJ. Endurance Training at Altitude. High Altitude Medicine & Biology. 2009;10(2):135-148. doi:10.1089/ham.2008.1092

- Rønnestad BR, Mujika I. Optimizing strength training for running and cycling endurance performance: A review: Strength training and endurance performance. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2014;24(4):603-612. doi:10.1111/sms.12104

Photo by Nick Wood on Unsplash