The second article in our exercise supplementation series will cover creatine. With its usage dating back to the mid-1800s,1 creatine is one of the most widely used and well-studied supplements on the market. Hereon, we will discuss its efficacy on sporting performance, and how one may use creatine in a practical setting.

What is creatine?

Discovered in 1832 and routinely studied since the 1920s, it was not until the 1990s that research on exercise and creatine began, which in conjunction with success testimonials from athletes competing in the Barcelona Olympic Games in 1992 led to its mainstream popularity.2,3,4 A 2001 paper found that in a sample of ~14,000 American college athletes, ~13% had used creatine within the preceding 12 months, with individual sports ranging between 10-30% for males. Notably, female usage only ranged between 0.2-3.8%.5,6

Creatine supplementation in practice

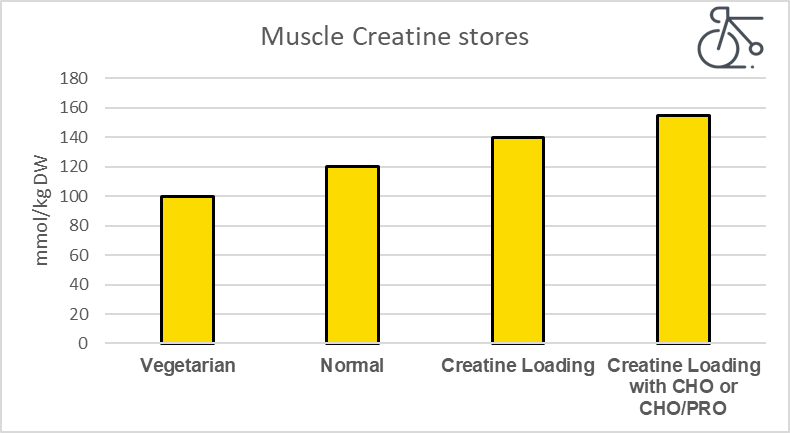

Creatine is synthesised naturally in the body at about 1 gram per day, with an additional 1-2 grams coming from dietary meat consumption.3 As such, vegetarians generally have lower creatine levels.7 It is difficult to saturate the creatine stores through diet alone, creatine supplementation increases muscle creatine content by 20-40%, mainly dependent on starting levels, but also on what it is co-ingested with.6

The International Society of Sports Nutrition (ISSN) recommends:6

A) A loading phase with 5 grams of creatine (or 0.3g/kg body weight) four times daily for 5-7 days to saturate the creatine stores, followed by a maintenance phase of 3-5 grams of creatine daily.

OR

B) Daily ingestion of 3-5 grams of creatine.

Protocol A results in saturated creatine stores within a week whereas it takes 3-4 weeks for protocol B to saturate the creatine stores, leading to a delayed benefit of the supplement for the latter. Following cessation of creatine supplementation, it takes 4-6 weeks for the creatine stores to return to baseline.6 From a practical standpoint, this also means that missing a few daily doses probably won’t affect neither creatine stores nor any performance benefits.

Co-ingesting creatine with carbohydrates or carbohydrates and protein has been shown to promote greater creatine retention and thereby increase the stores even further, as can be seen in Figure 1.8,9

Figure 1. Muscle creatine stores following different dietary patterns. Adapted from Kreider and Jung (2011)10 (CC BY 4.0).

Benefits of creatine supplementation

Creatine loading can acutely enhance the performance of sports involving repeated high-intensity exercise (eg, team sports), as well as the chronic outcomes of training programmes based on these characteristics (eg, resistance or interval training), leading to greater gains in lean mass and muscular strength and power.

International Olympic Committee.11

Muscle strength and power

The effects of creatine supplementation on strength and power have been extensively studied. When grouping the data from multiple studies, creatine was found to confer moderate improvements over placebo in lower body strength, with improvements of 8% in squats and 3% in leg press, measured as 1-rep maximum (1RM). Further, indices of power such as jump height improved more from supplementation than placebo.12 Similarly, improvements in upper-body strength are also improved by creatine supplementation, with a 5.3% increase over placebo in bench press.13 These studies all looked at chronic effects following an extended training period with or without creatine supplementation and not acute performance. In the studies analysed, variables such as sex, age, creatine dosage, training status, or study length did not affect the performance benefits.

Muscle mass

Increments in lean mass of 1-2% of the body weight occur within days following the creatine loading phase because of water retention. Nevertheless, one meta-analysis found that in a group of studies averaging 7.5 weeks in duration, creatine resulted in a net gain of 0.36% increase in lean mass per week.14 Creatine is quite possibly the most effective legal supplement out there for building muscle mass.14

Endurance sports

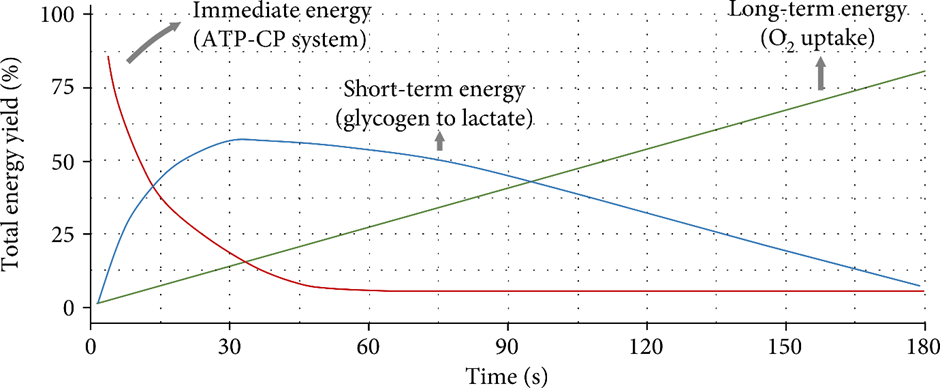

The creatine system is the predominant energy system within the first 10 seconds of exercise, providing ATP for the working muscle in the absence of oxygen. Therefore, creatine is not generally thought of in the context of endurance sports where the duration of competition can be multiple hours. Despite the slight weight increase that may be detrimental to some weight-bearing endurance sports, supplementation can be beneficial in certain instances.

As a general principle, if the event is shorter and of high intensity, the greater the potential performance benefit from an increased creatine store. As can be seen in Figure 2, the relative contribution of the creatine system (ATP-CP system) is the greatest in the first 15 seconds and diminishes to close to zero after 35 seconds. In a study by Smith et al. conducting multiple time-to-exhaustion (TTE) trials designed to elicit failure at four time points between 90-600 seconds at different intensities, creatine supplementation increased the work completed at all durations, with a progressively greater improvement for shorter duration trials.15 TTE tests are inherently unreliable and may yield highly variable results even when repeating the same conditions with the same subjects. Further, TTE tests are generally thought to measure exercise capacity, as opposed to exercise performance, which is a small yet important distinction.16

Figure 2. Adapted from Huertas et al. (2019)17 (CC BY 4.0).

Even though creatine supplementation has proven successful in short TTE trials, this may not translate to time trial (TT) performance. For example, Balsom et al. found that 6km running TT performance in undulating terrain deteriorated by ~2% following creatine loading, probably due to the elevated body mass, which increased by ~1kg.18 TT tests on a cycle ergometer revealed no improvement from creatine supplementation over a 20-minute trial and a 120 km trial.19,20

Some promising results have been reported in shorter time trials. For example, 400-metre swimming performance and 1000-metre rowing ergometer performance both increased following supplementation.21,22 Interestingly, the performance gains were driven by faster end splits. Likewise, the aforementioned 120 km TT included alternating 1 km and 4 km sprints every 10 km throughout the test, where the final two sprints yielded higher power outputs.20

Short-term creatine interventions also improve repeated sprint ability, as is highly relevant, particularly in team sports that are intermittent in nature. Specifically, mean power output is increased over the repeated high-intensity surges. Peak power and sprint running speed were not affected, as well as measured fatigue during the repeated sprint tests.23 Meaning, the subjects were able to perform more high-intensity work for the same levels of fatigue.

Altogether, for steady-state endurance events lasting more than a few minutes, it is unlikely that creatine improves performance. In weight-bearing sports, it may even be detrimental. In trials lasting up to a few minutes or in sports with elements of sprinting or intermittent high-intensity surges, the available evidence would suggest that creatine improves performance.

Other effects

Stored carbohydrates in the form of muscle glycogen can limit endurance performance. Creatine supplementation in conjunction with carbohydrates has been found to increase glycogen stores.24 This would enable the athlete to perform a higher training load before reaching fatigue, as well as work at a high intensity for longer following carbohydrate loading with creatine.

Mechanisms of action

The food we consume provides the energy that enables movement. The body does not use the macronutrients in their natural form though, instead, they are converted into a molecule called adenosine triphosphate, ATP for short. ATP consists of an adenosine molecule that carries these three phosphates. When the muscle contracts, the bond between the adenosine and phosphates is broken and energy is freed which enables the movement. One gram of glucose yields ~36 ATP molecules.25 ATP is however only found in extremely small quantities, sufficient for ~2 seconds of work. Instead, the phosphates are stored in larger quantities on creatine molecules, creating creatine phosphate (PCr), which regenerates the adenosine into ATP and thereby enables sustained muscle contractions.26 Increased creatine stores lead to a larger “reserve” capacity and thereby enable a few extra seconds of high-intensity work.

Safety

Since its popularisation in the 1990s, more than 1000 studies have been conducted on creatine, with the only consistent side-effect being temporary weight gain (as creatine binds water, about 0.5 – 1.0 L). In otherwise healthy people, doses of up to 0.8 g/kg/day for up to 5 years have consistently been proven safe and provide numerous health and performance benefits.6

The International Society of Sports Nutrition concludes6

- Creatine is the single most effective supplement available for athletes aiming to increase high-intensity exercise and lean mass during training.

- Creatine is safe, with no compelling evidence that long-term use (up to 30g/day for 5 years) has any detrimental effects on otherwise healthy individuals.

- Creatine monohydrate is the most extensively studied and effective form of creatine for use in supplements.

- Combining creatine with carbohydrates or carbohydrates and protein increases creatine uptake in the muscle but does not necessarily increase high-intensity exercise work capacity.

- The quickest way of increasing muscle creatine stores is to consume ~0.3 g/kg/day of creatine monohydrate for 5–7 days followed by 3–5 g/day thereafter to maintain elevated stores.

References

- Wallimann T. Introduction – Creatine: Cheap Ergogenic Supplement with Great Potential for Health and Disease. In: Salomons GS, Wyss M, eds. Creatine and Creatine Kinase in Health and Disease. Subcellular Biochemistry. Springer Netherlands; 2007:1-16. doi:10.1007/978-1-4020-6486-9_1

- Momaya A, Fawal M, Estes R. Performance-Enhancing Substances in Sports: A Review of the Literature. Sports Med. 2015;45(4):517-531. doi:10.1007/s40279-015-0308-9

- Butts J, Jacobs B, Silvis M. Creatine Use in Sports. Sports Health. 2018;10(1):31-34. doi:10.1177/1941738117737248

- Trexler ET, Smith-Ryan AE. Creatine and Caffeine: Considerations for Concurrent Supplementation. Int J Sport Nutr Exerc Metab. 2015;25(6):607-623. doi:10.1123/ijsnem.2014-0193

- Green GA, Uryasz FD, Petr TA, Bray CD. NCAA Study of Substance Use and Abuse Habits of College Student-Athletes: Clin J Sport Med. 2001;11(1):51-56. doi:10.1097/00042752-200101000-00009

- Kreider RB, Kalman DS, Antonio J, et al. International Society of Sports Nutrition position stand: safety and efficacy of creatine supplementation in exercise, sport, and medicine. J Int Soc Sports Nutr. 2017;14(1):18. doi:10.1186/s12970-017-0173-z

- Burke DG, Chilibeck PD, Parise G, Candow DG, Mahoney D, Tarnopolsky M. Effect of Creatine and Weight Training on Muscle Creatine and Performance in Vegetarians: Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2003;35(11):1946-1955. doi:10.1249/01.MSS.0000093614.17517.79

- Greenwood M, Kreider R, Earnest C, Rasmussen C, Almada A. Differences in creatine retention among three nutritional formulations of oral creatine supplements. Published online May 2003.

- Steenge GR, Simpson EJ, Greenhaff PL. Protein- and carbohydrate-induced augmentation of whole body creatine retention in humans. J Appl Physiol. 2000;89(3):1165-1171. doi:10.1152/jappl.2000.89.3.1165

- Kreider RB, Jung YP. Creatine supplementation in exercise, sport, and medicine. J Exerc Nutr Biochem. 2011;6(1):53-69. doi:10.5717/jenb.2011.15.2.53

- Maughan RJ, Burke LM, Dvorak J, et al. IOC consensus statement: dietary supplements and the high-performance athlete. Br J Sports Med. 2018;52(7):439-455. doi:10.1136/bjsports-2018-099027

- Lanhers C, Pereira B, Naughton G, Trousselard M, Lesage FX, Dutheil F. Creatine Supplementation and Lower Limb Strength Performance: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analyses. Sports Med. 2015;45(9):1285-1294. doi:10.1007/s40279-015-0337-4

- Lanhers C, Pereira B, Naughton G, Trousselard M, Lesage FX, Dutheil F. Creatine Supplementation and Upper Limb Strength Performance: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Sports Med. 2017;47(1):163-173. doi:10.1007/s40279-016-0571-4

- Nissen SL, Sharp RL. Effect of dietary supplements on lean mass and strength gains with resistance exercise: a meta-analysis. J Appl Physiol Bethesda Md 1985. 2003;94(2):651-659. doi:10.1152/japplphysiol.00755.2002

- Smith JC, Stephens DP, Hall EL, Jackson AW, Earnest CP. Effect of oral creatine ingestion on parameters of the work rate-time relationship and time to exhaustion in high-intensity cycling. Eur J Appl Physiol. 1998;77(4):360-365. doi:10.1007/s004210050345

- Currell K, Jeukendrup AE. Validity, Reliability and Sensitivity of Measures of Sporting Performance: Sports Med. 2008;38(4):297-316. doi:10.2165/00007256-200838040-00003

- Huertas JR, Casuso RA, Agustín PH, Cogliati S. Stay Fit, Stay Young: Mitochondria in Movement: The Role of Exercise in the New Mitochondrial Paradigm. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2019;2019:1-18. doi:10.1155/2019/7058350

- Balsom PD, Harridge SDR, Soderlund K, Sjodin B, Ekblom B. Creatine supplementation per se does not enhance endurance exercise performance. Acta Physiol Scand. 1993;149(4):521-523. doi:10.1111/j.1748-1716.1993.tb09649.x

- van Loon LJC, Oosterlaar AM, Hartgens F, Hesselink MKC, Snow RJ, Wagenmakers AJM. Effects of creatine loading and prolonged creatine supplementation on body composition, fuel selection, sprint and endurance performance in humans. Clin Sci Lond Engl 1979. 2003;104(2):153-162. doi:10.1042/CS20020159

- Tomcik KA, Camera DM, Bone JL, et al. Effects of Creatine and Carbohydrate Loading on Cycling Time Trial Performance. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2018;50(1):141-150. doi:10.1249/MSS.0000000000001401

- Anomasiri W, Sanguanrungsirikul S, Saichandee P. Low Dose Creatine Supplementation Enhances Sprint Phase of 400 Meters Swimming Performance. 2004;87.

- Rossiter HB, Cannell ER, Jakeman PM. The effect of oral creatine supplementation on the 1000‐m performance of competitive rowers. J Sports Sci. 1996;14(2):175-179. doi:10.1080/02640419608727699

- Glaister M, Rhodes L. Short-Term Creatine Supplementation and Repeated Sprint Ability-A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Int J Sport Nutr Exerc Metab. 2022;32(6):491-500. doi:10.1123/ijsnem.2022-0072

- Roberts PA, Fox J, Peirce N, Jones SW, Casey A, Greenhaff PL. Creatine ingestion augments dietary carbohydrate mediated muscle glycogen supercompensation during the initial 24 h of recovery following prolonged exhaustive exercise in humans. Amino Acids. 2016;48(8):1831-1842. doi:10.1007/s00726-016-2252-x

- Hargreaves M, Spriet LL. Skeletal muscle energy metabolism during exercise. Nat Metab. 2020;2(9):817-828. doi:10.1038/s42255-020-0251-4

- Martini FH, Nath JL, Bartholomew EF. Fundamentals of Anatomy & Physiology. Vol 2018. 11th ed. Pearson

Photo by Aleksander Saks on Unsplash